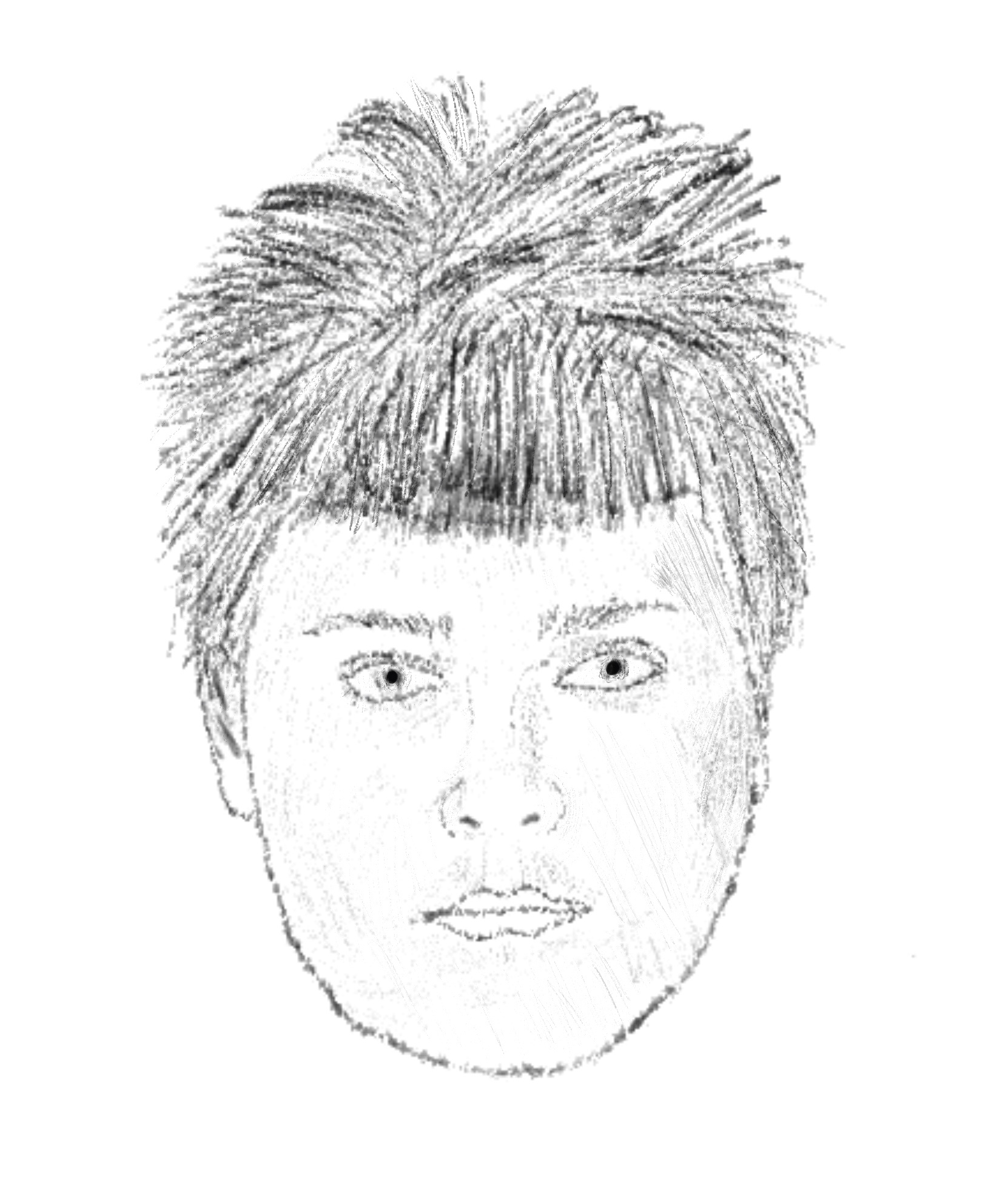

Tse Man Pok, “Apok” the nurses would call him, that characteristic prepending of the “A” to his first name never failed to confuse me, an idiosyncrasy of the Cantonese dialect, though I can’t deny it was a handsome transformation; it served, in a strange way, to give him more character. Almost like a title. He was a frail, skinny man, who stood no more than five feet ten inches at a hunched posture. He had thin lips framed by a wispy greying mustache, between which a long tongue was almost perpetually stuck out, undulating, and a head of long, thick, salt and pepper hair. He was certainly a curious man, who had an even more curious gait about him. He always seemed to walk with intent: hands behind his back, he would march around the psychiatric ward, H4, giving a peculiarly languid glance to anyone who was in his path. Guardian of the H4 toilets I would call him, for that is where he spent most of his time, if he wasn’t already sleeping or on the patrol. He would squat in the back of the toilets, his kingdom, always muttering some mantra to himself. Hitherto our being enemies, we were mostly on friendly terms. I would give him snacks, a currency of sorts in his limited world, in exchange for his wisdom, or at least that is what I would call his subsequent utterings, albeit in a language I couldn’t understand, Cantonese. He didn’t have any teeth, so he couldn’t eat much, and was restricted to a liquid diet. When he retired from the toilets for the day, he was a philosopher in my eyes. Many great dialogues occurred between us. However, one day, he threw an empty milk carton at me and hit me, for no obvious reason – perhaps he was stricken by a bout of confusion, for he was old, and it was about that time one can be cursed by such spells – before retreating to his kingdom. I never took him for a violent man, despite his military demeanor. Shortly after, he was restrained and transferred to another ward. Poor old man.

When I wrote these pages, or rather the bulk of them, I was living under the welfare of my parents in their flat in Hong Kong. After high school – and this is in large part owing to the circumstances that lay in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, though I won’t outright blame it, but also due to my temperament, which is one of melancholy – I lived effectively, as a NEET, a shut-in, a hikikomori (a hiki, as they are known colloquially online, which is how I will refer to myself, hereafter); whatever you would like to call a person who almost never ventures past the safety of their front door, usually for reasons of chronic and intense social anxiety – sometimes for months on end, or in my case, even years – is fixated on internet culture, terminally online, and most importantly, alone. The socially isolated, human waste, and the like.

People from the imageboards would often ask me if I did not feel lonely. I did, and it was that way for a long time. So intense a frustration was my loneliness that I was unable to focus on anything else, one that served to torment every fiber in my body. And so harsh was its gnaw that it was unbearable, one whose teeth had pierced through every thread of my mind. From the moment of my conception, I say to myself, sometimes half in jest, but never without a hint of realism, I am destined to a long and unforgiving path of infinite solitude, albeit one flecked golden with small bursts of life. I aim to document that journey, to make sense of what happened to me, what went wrong in my life, the steps I can take to better it, and serve as a cautionary tale or an antidote for anyone who finds themselves in a similar situation.

Originally, my suffering, the desire to understand it, and creativity all served to put a pen in my hand, the object of which was to write of my time in the psychiatric wards H4, K3, and K4 of the Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital, which I would come to know over the course of about a year; however, in order to better understand my anguish, I saw it more fitting to write of this phase of insanity in its entirety. It is important to note that the events in this book are taken strictly from reality; nevertheless, grant me the ability to embellish some parts of this account, for literary purposes. Though I recognize that I am, at best, a second-rate writer, I will try my absolute hardest to be as objective as possible in the recording of my own subjective experience, all the while being, hopefully, the least bit entertaining, so forgive my ability – or lack thereof. Also, I genuinely believe that seldom does anyone shed new light on the human condition; everything profound to be thought has already been, for the most part, stated, and anyone who says otherwise is merely spouting diluted remasters of older philosophical ideas. At any rate, please read these next pages carefully.

The state of being a hikikomori, or “hikidom” is a Japanese term etymologically derived from “hiku” (“to pull back”) and “komoru” (“to seclude oneself”). It is a form of severe social withdrawal, specifically precipitated, I believe, by the advent of the internet and other related technologies in combination with, but not limited to biological and social factors as well as psychiatric states such as depression, personality disorders, PTSD and trauma, social anxiety, and schizophrenia. Hikidom doesn’t come about spontaneously. The process is one of a slow descent into social alienation, which in turn leads to self-isolation, ultimately ending in a vicious cycle that serves to perpetuate the state. There’s typically a major event in one’s life that triggers this trajectory; however, I recognize that it can also be the result of multiple traumatic events that occur in quick succession. In my case, I believe it was brought about by my failure to transition into adulthood, and more specifically, my failure to become independent. Moreover, I was not ready for university and the life it entailed. Even so, this type of failure doesn’t come out of the blue, rather it is one that is crafted meticulously by unique circumstances, and much more, was a symptom of a larger problem. That is not to say that one is destined to hikidom from the get-go, though some people are more predisposed to the condition than others, but once the process gets into gear, it is a very hard one to stop, especially if you are of weak will, as people susceptible to hikidom typically are, for it is a process that pervades all aspects of one’s life; its all-encompassing nature serves to weigh down on the person’s psychological state, until they inevitably crumble, break, collapse. I remember the day I realized I was a hiki, more accurately, the realization took place over the course of about a month, but the feelings of shame, self-hatred, loneliness, and despair peaked on a particular day, a day I remember all too well, the day I attempted suicide.

Before I talk of that fateful day, however, I ought to provide you with some context. I’m sure that the astute reader has already gathered that I had lived as a hiki and spent some time in various psychiatric wards, but for the sake of being comprehensive, I should answer the following questions that I see important: what was my childhood like? More specifically, did I experience any traumatic events, physical or emotional abuse for instance, be it within school or back at home? What were the dynamics like between my friends and family during this time? How did my relationship with technology evolve over time?

Even if I would have known of the days that would lead up to my hikidom, what would follow in its path, its reign, its nature, and its “end”, I am convinced that nothing could have prepared me for such a stark and hideous change in my life, during which I committed sins of the soul, for which I cannot atone, and as a result, my mind and body suffered the consequences. I became rotten. While hikidom can seemingly resolve itself, I still believe a segment of it, however miniscule, can remain intact within you for the rest of your life; and so, you are continually stirred by this force – ones whose roots are laid within the depths of your consciousness and that no amount of psychotherapy or concoction of drugs can cure – it is a damning one, yes.

Over the course of my hikidom, I had many case doctors. However, one doctor, Dr. Mei, the most notable of the lot, who always spoke in a tone of sympathy, which never failed to move me, was certainly a comely woman underneath that mask. I’ll admit that I had a bit of a crush on her. Perhaps it was owing to that characteristic clinginess of patients afflicted by BPD. I don’t know. Nevertheless, I seem to fall in love with every woman that comes into my life, however insignificant a role they play. She stood rather tall for a Chinese woman, and as such, seemed to command a certain respect, one that was felt by everyone in the room. And of course, her being a doctor certainly helped support that fact. If you’re reading this, Dr. Mei: hello! I hope you’re doing well. You were always very understanding about my concerns regarding my mental health, a compassion that most of my doctors didn’t extend to me for they wrote me off as crazy. So, thank you, really.